BACKGROUND

1 – E-commerce in Europe is steadily gaining market share as more and more

businesses and consumers are conducting transactions by electronic means.

2 – E-commerce is therefore one of the priorities of this new legislature for the

European Commission, which wishes to draw up a framework defining the

responsibility and obligations of intermediaries.

3 – The project for an enlarged European legislation included in the package entitled

« DIGITAL SERVICE ACT » is designed to strengthen the internal market while

guaranteeing a high level of consumer protection. It also aims to safeguard the

activities of economic operators and the economy of European micro, small and

medium-sized enterprises, to provide them with greater legal certainty, to give them

confidence when using digital services and to ensure transparency of content and

information.

4 – The platforms provide a very wide range of services by ensuring access, hosting,

transmission or indexing of the content of products and services offered by third parties. It is therefore clear that the drafting of this future legislation will have to include a revision of the E-Commerce Directive in order to clarify the transparency obligations of platforms and to ensure the fight against counterfeiting and illegal content online.

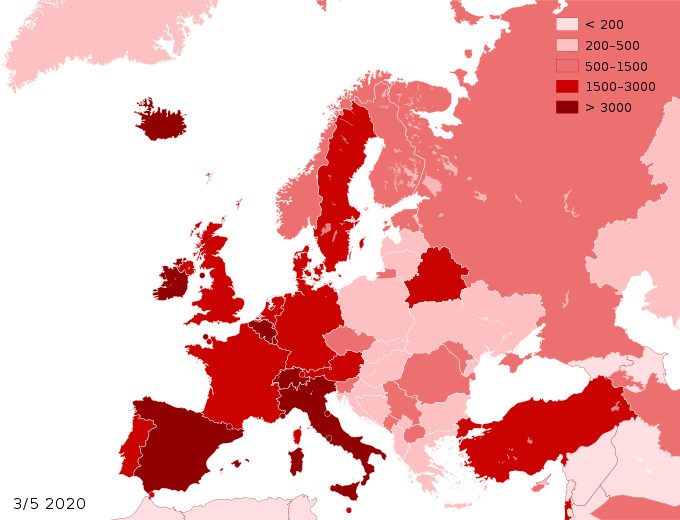

STATE OF PLAY

5 – E-commerce has become a real source of profit for many companies and the offer

now covers all market sectors whether it is for everyday products, capital goods or

services. It is considered faster, more practical and sometimes more economical. In

2019, 53% of Internet users made at least one online purchase. E-commerce is

therefore having the effect of considerably changing the behaviour of distributors and

consumers: it is accelerating the decline of small traditional retail businesses, but has

spectacularly opened up the frontiers of international trade. China and the United

States, for example, have so far taken the lion's share of e-commerce growth, at the

expense of Europe in particular.

THE EUROPEAN UNION AND ELECTRONIC COMMERCE

– Future legislation should be built around two European texts that need to be

developed:

a) – The E-commerce Directive

b) – The platform to business regulation

From the E-commerce directive, it is clear that the text should retain the ban

on generalised surveillance, while being aware that it will be absolutely

necessary to update this directive.

From the "platform to business" regulation which governs the relationship

between online platforms and user businesses, the future proposal should

strengthen the promotion of fairness and transparency between user

businesses and online intermediation services.

7 – Already the WTO, aware of the exponential growth of this world market, has

begun negotiations with some of the EU Member States in an attempt to regulate this

phenomenon, which remains largely out of control. It should be noted that the rules of

competition law are already a means of understanding the economic relations

between certain major commercial platforms and companies or creators of protected

content (see the recent Google decision by the French competition authority on the

neighbouring right of press publishers).

THE POSITION OF THE INSTITUTE FOR DIGITAL FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

As a preamble, the Institute considers that it is rare today for a company to rely

on only one type of intellectual property right, it generally has at its disposal a

whole range of intangible economic rights, which is why the Institute will pay

attention to all these rights.

8 – IDFrights considers that online sales are not limited to large and renowned

commercial platforms and are increasingly popular and used by small and medium

sized companies. The latter are a real opportunity for our capacity for innovation.

9 – iDFrights underlines that online sales are a very important vector for the

development of the European economy. Therefore 'we must accompany this

economy by guaranteeing a high level of protection and security for users, but also a

coherent and transparent legal framework for businesses. It also needs to be

provided with a technological environment which is based on the principle of

interoperability between the players concerned.

10 – iDFrights reminds that even in the context of legal transactions, the online

marketplace also has grey areas. For example, some websites or online markets do

not hesitate to use these legal means to sell counterfeit products or download

illegally (music, videos or games). The Institute insists that specific provisions are

needed, especially as about half of the national court decisions concern injunctions

against Internet service providers to stop and/or prevent IPR infringements by third

parties.

11 – iDFrights insists on clarifying the nature of content hosting intermediaries and in

particular the distinction between passive intermediaries (benefiting from the limited

liability of the platforms) and active platforms responsible for the communication to

the public of the content posted by their users. The latter are no longer likely to

benefit from the limited liability regime within the meaning of Articles 14 and 15 of the

e-commerce Directive. To this end, the new legal regime should seek to better

understand and promote the category of platforms that structure or are essential for

online commercial exchanges.

12 – iDFrights insists on the need to explicitly mention in the terms of contracts and

the general conditions accompanying them, the obligation for service providers not to

retain sensitive data and to comply with the European Directive on Unfair Contract

Terms, the Consumer Rights Directive and the DPMR.

13 – iDFrights points out the importance of transparency requirements in order to

avoid any ambiguity in the terms of contracts and general conditions, which can

affect consumer choice or influence consumer behaviour. The Institute considers that

the closed system of operation of certain platforms may constitute an obstacle to

freedom of opinion and expression.

14 – iDFrights points out that, as regards the operation of an e-commerce platform, the

use of any product, service identical or similar distinctive sign to registered trade marks

which have a reputation in the Union presents a likelihood of confusion in the mind of the

public and damage to the trade mark itself. The provider must, as soon as he becomes

aware of this, remove the information or the product as soon as possible or make access to it

impossible.

15 – iDFrights advocates the need to strengthen the role of online intermediaries in

the fight against illegal content. It specifies in particular that any removal or

deactivation of access to illegal content must be carried out as soon as it is identified

in order to preserve quality and secure commercial exchanges, but recalls that this

removal or deactivation must be carried out in compliance with the fundamental

rights and legitimate interests of consumers.

16 – iDFrights notes, however, that in the context of the development of online

services and in a globalised digital world, the principle of the law of the country of

origin may prove to be inappropriate for reasons recognised as such by the case law

of the Court of Justice, particularly as regards consumer protection and intellectual

property. The objectives of these platforms are essentially guided by the search for

countries where regulations are less restrictive in a number of areas, whether fiscal

or related to illicit or illegal activities. It would therefore probably be useful to

consider whether the country of destination principle would be preferable, which

would make it possible in the future to overcome certain shortcomings in the principle

of the law of the country of origin for the reasons mentioned above.

CONCLUSION

iDFrights believes that the responsibility of the European Institutions, in the

elaboration of the DSA, is fundamental. Indeed, at both ends of the chain that was

the E-commerce Directive in 2000 and the "platform to business" regulation in 2019,

it is a question of creating a text that gives rise to a third European way. This third

way must have as its central axis the industrial development of European companies,

and transparency that respects users. In particular, it should not in any way call into

question the freedom and openness of our economy, as long as it is framed by real

regulation.

From experience, Europe has learned that no text application is sustainable without

education in these texts. Since they concern the younger generations in the long

term, it is towards them that educational efforts must be made and the means must

be provided. Nothing is concretely achieved in the long term if we forget that the

future is in the hands of the younger generations.

Nor will anything be achieved without political will at Community level and without

investment. It is the efforts of our start-ups and our European researchers that must

above all be rewarded and remunerated.

![[DSA, AI Act] Régulation, et si l’Europe avait raison ? Podcast les Eclaireurs du Numérique avec Jean-Marie Cavada](https://idfrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/8c234391-01e8-40d4-9608-4ea6c80d4f11-440x264.jpg)